Faustino Cordón, a forgotten genius of science: “I was a one-eyed, one-armed Bolshevik with a gun.”

Madrid, July 1936. A young man named Faustino Cordón, recently arrived in the city, attends one of the first organizational meetings of the Fifth Regiment. Vittorio Vidali, a communist militant nicknamed Commander Carlos , asks the audience:

-Who among you is an expert in explosives or chemists?

No one answers, so Cordón launches:

-I'm not a chemist, but I am a pharmacist.

There is a wave of laughter, but Vidali insists:

-Do you know how to poison water, make bombs, howitzers, manufacture gases?

Cordón replies: “Does anyone here know how?” And, as the answer was negative, he continued: “Well, I know how to make trinitrotoluene.” And so he was appointed chief of weapons of the fledgling Fifth Regiment. He was twenty-seven years old.

The scene is recounted in the recent book Faustino Cordón, the Rebellious Biologist (Garaje), in which one of his daughters, Elena, and journalist Elvira de Miguel compile the vast written and audio material left behind by one of the most atypical and unknown scientists in the history of Spain. One-eyed and nearly maimed by war accidents, Cordón wanted to be an artist, devoted himself to drawing, lived in Paris as a bohemian, and met Picasso . One day, he decided to go to Madrid to study pharmacy and serve the communist cause, which he had just embraced. Almost miraculously saved from being shot, he survived by doing science as an internal exile during the Franco dictatorship, memorized Darwin's theory of evolution, and launched himself into building his own theoretical edifice to explain the origin of life in all its strata, composing a monumental work of evolutionary philosophy unique in the Spain of that era.

Cordón, the son of a liberal family from Extremadura who owned a large estate that his father gave to the peasants in 1936, soon renounced Stalinist communism, but led the first Spanish scientific visit to the USSR after Franco's death. During the Transition, he was a figurehead of very clear ideas about who we are and where we come from, which he expounded in his most famous popular book, Cooking Made Man , and in his journalistic articles, many of them in EL PAÍS , where he said things like the fact that humans today are the same as those painted by the bison of Altamira thousands of years ago, because we are united by technology and language.

Shortly after accepting his position as chief of weapons, a former classmate from El Pilar school asked Faustino to save his house—a chalet in the heart of the Salamanca district—from the "popular fury." The pharmacist told him not to worry: he would take it himself to set up the explosives manufacturing laboratory. There, he and his collaborators worked tirelessly, plagued by horrible headaches caused by dynamite, which is a vasodilator. One day, there was a sabotage attack and the entire arsenal blew up. The terrible explosion took out one of Cordón's brothers and two of his closest collaborators, León Meabe and Leo Fleischman, and injured two of his sisters. A splinter of shrapnel pierced Cordón's eye and stopped just millimeters from his brain, leaving him blind for life, but miraculously saving his life.

In the final days of the Civil War, in the port of Alicante , Cordón threw into the water a cardboard suitcase filled with documents about the Fifth Regiment. These documents were intended for Antonio Machado , who was to write a eulogy on his body. The project never came to fruition, as Machado died in February 1939. In return, Cordón saved his life for the second time, as the Nationalist soldiers never knew he was the mastermind of the communist military's weapons development. Despite this, he spent more than a year in concentration camps and prisons, where, despite the hunger, he insisted on continuing to study whatever was available, starting with an English grammar book he had found lying around in the port of Alicante, from which ships were no longer departing and where he witnessed three suicides on the same day. A year later, in September 1940, thanks to his family bribing the judge, Cordón was released and began his atypical scientific career.

The pharmacist got a job at Zeltia laboratories in Porriño, Galicia. Upon arrival, he realized that the company was full of repressed Republican scientists who survived in internal exile and provided useful, cheap labor under the command of Professor Fernando Calvet . Zeltia specialized in the production of compounds derived from animal glands. In the midst of the postwar period, Cordón's first scientific project was to understand why shipments of insulin arriving from Switzerland spoiled within a few days. Some time later, he managed to isolate the molecule responsible, which he called insulinase. Thanks to his work and that of his colleagues, Zeltia patented several pharmaceutical specialties such as ephedrine, digitalis, liver extracts, folliculin, purpuripán, and several vitamins. The company was later absorbed by its subsidiary, the current PharmaMar .

During those years, Cordón suffered a setback that would determine his career as a scientist outside the academic system. Despite having received a prestigious Fulbright scholarship to study in the United States, he was unaware of why he was being denied the opportunity to travel. Cordón protested and went to the office of José María Albareda , a pharmacist linked to Opus Dei and secretary general of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), founded by Franco in 1939 for "the restoration of the classical and Christian unity of the sciences." "He was a sort of monk in civilian clothes who decided on the purges. He received me icily in his office behind a monastic table, with a Christ on top of a skull. He listened attentively to my arguments, without saying a word, but it was all in vain; I was the only one who wasn't given a passport," Cordón explained to his daughter Inés in 1994.

The scientist went on to work in Madrid at the Institute of Biology and Serum Therapy , one of the leading vaccine and medical biological molecule factories of the time. In addition to continuing to work as an experimental scientist, Cordón employed political prisoners at the facility after they had served their sentences.

“He was a cheerful person, brimming with physical energy that he poured into his work, and with an astonishing confidence in his biological theory, curiously coupled with a great deal of humility,” summarizes his daughter Elena. The word that best describes his scientific activity is “frenetic,” according to journalist Elvira de Miguel.

Cordón translated important scientific works from German into Spanish during those years, but his main objective was to develop his own treatise on the origin of life. According to his biography, in the 1950s, Cordón discovered the ability of certain proteins to multiply by themselves, which led him to consider them the basic fundamental units of life, naming them basibiones. The idea, still heterodox today, was ignored until 1995, when neurologist Stanley Prusiner discovered prions, proteins capable of multiplying and evolving on their own, and which cause brain diseases such as mad cow disease, a discovery that earned him the Nobel Prize in Medicine two years later.

Despite his isolation, Cordón received unexpected support, such as that of Juan Huarte Beaumont , owner of an important construction company that ended up being the H of OHL, who hired him to write his great work: Tratado evolucionista de laboratorio . In the 60s this collaboration ended, but Cordón was then approached by Ernestina González, a librarian from Burgos and partner of Leo Fleischman , considered the first American volunteer to fall in the Civil War, who came from a wealthy family in New York and died precisely in the explosion of the bomb factory that Cordón ran during the War.

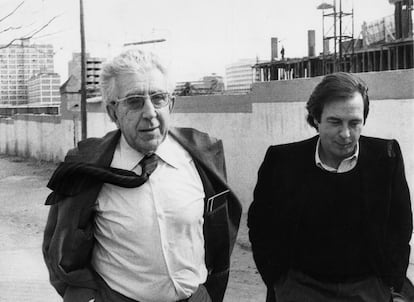

“With Faustino, it always seemed like you were talking to someone your own age, even though we were 60 years apart,” recalls neuropathologistAlberto Rábano , of the CIEN Foundation, who was a disciple of Cordón in the 1980s. “He was very much on the fringes of official science, and quite despised by the Franco and post-Franco universities,” he recalls.

Rábano compiled the bibliography for the second volume of Cordón's evolutionary work, which dealt with animals. "He had a timely life and was in a great hurry to finish his work. We, who were young, suggested that he conduct experiments, but he, although he had been a great experimental scientist, no longer wanted to leave the theoretical realm," he recalls.

Cordón managed to finish the second part of his work, which he presented in 1990 at the building of the former General Directorate of Security on Madrid's Puerta del Sol, where he had once been detained and which now housed the Madrid Regional Government. He died in December 1999, just shy of 91, without finishing the third part, dedicated to humans. "There is no other author on par with Cordón in this field in Spain. It's worth recovering," says Rábano, who also remembers his mentor for his sense of humor. One of his favorite jokes was to say: "Now you see me as very civilized, but I was a one-eyed, one-armed Bolshevik with a gun."

Biologist Arcadi Navarro , ICREA researcher and director of the Pasqual Maragall Foundation, read Cordón's work while he was studying for his degree and never forgot it. "He used groundbreaking concepts that weren't appreciated because readers weren't ready," he explains. After his death, all the funds from the foundation Cordón had created thanks to Ernestina González went to the Pasqual Maragall Foundation, which had been a friend of Cordón and his wife, María Vergara. "There are three generations of conscientious citizens—Fleischman, Cordón, Maragall—who donated everything to the collective project of science," Navarro emphasizes.

Cordón's personal archive, containing hundreds of letters, photographs, and thousands of notes, has been housed at the National Library since 2018. Much of his scientific, journalistic, and autobiographical work can be accessed free of charge on the website faustinocordon.org , created by his daughters.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Fe79%2F6cf%2F43a%2Fe796cf43a0d16b5e6b66e95530ee4cc8.jpg&w=3840&q=100)